18

апр

Blastomycosis In Humans

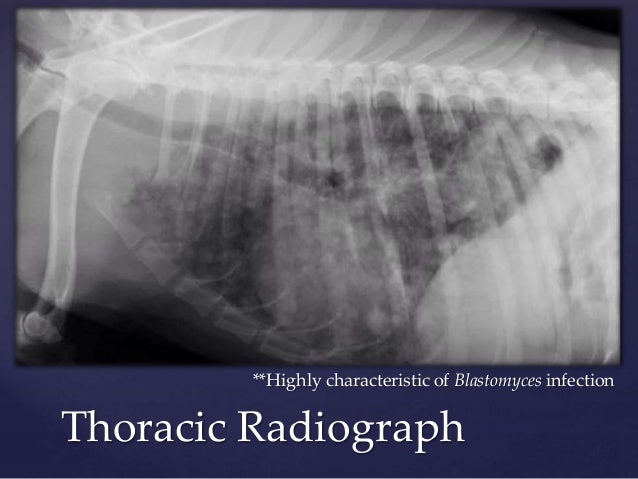

Posted:adminNot to be confused with 'South American blastomycosis'. BlastomycosisOther namesNorth American blastomycosisSkin lesions of blastomycosis.Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by inhaling spores. If it involves only the lungs, it is called pulmonary blastomycosis.

Blastomycosis infections are most common in dogs between 1 and 5. Humans have to contract the fungal disease the same way as dogs:. Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic to areas. A relationship between canine blastomycosis and human disease.

Only about half of people with the disease have symptoms, which can include, weight loss, chest pain,. These symptoms usually develop between three weeks and three months after breathing in the spores.

In those with, the disease can spread to other areas of the body, including the skin and bones.Blastomyces dermatitis is found in the soil and decaying organic matter like wood or leaves. Participating in outdoor activities like hunting or camping in wooded areas increases the risk of developing blastomycosis. There is no vaccine, but the disease can be prevented by not disturbing the soil. Treatment is with for mild or moderate disease and for severe disease. With both, the duration of treatment is 6–12 months. Overall, 4-6% of people who develop blastomycosis die; however, if the central nervous system is involved, this rises to 18%.

People with or on have the highest risk of death at 25-40%.Blastomycosis is to the eastern United States, especially the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, the Great Lakes, and the St. Lawrence River.

It is also endemic to some parts of Canada, including Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba. In these areas, there are about 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 per year.

Blastomycosis was first described by Thomas Casper Gilchrist in 1894; because of this, it is sometimes called 'Gilchrist's disease'. Large, broadly-based budding yeast cells characteristic of Blastomyces dermatitidis in a GMS-stained biopsy section from a human leg.Inhaled conidia of B. Dermatitidis are by neutrophils and macrophages in alveoli. Some of these escape phagocytosis and transform into yeast phase rapidly. Having thick walls, these are resistant to phagocytosis and express glycoprotein, BAD-1, which is a virulence factor as well as an epitope.

In lung tissue, they multiply and may disseminate through blood and to other organs, including the skin, bone, genitourinary tract, and brain. The incubation period is 30 to 100 days, although infection can be asymptomatic. Diagnosis Once suspected, the diagnosis of blastomycosis can usually be confirmed by demonstration of the characteristic broad based budding organisms in sputum or tissues by KOH prep, cytology, or histology.

Tissue biopsy of skin or other organs may be required in order to diagnose extra-pulmonary disease. Blastomycosis is histologically associated with granulomatous nodules. Commercially available urine antigen testing appears to be quite sensitive in suggesting the diagnosis in cases where the organism is not readily detected. While culture of the organism remains the definitive diagnostic standard, its slow growing nature can lead to delays in treatment of up to several weeks. However, sometimes blood and sputum cultures may not detect blastomycosis. Treatment given orally is the treatment of choice for most forms of the disease.

May also be used. Cure rates are high, and the treatment over a period of months is usually well tolerated.

Is considerably more toxic, and is usually reserved for immunocompromised patients who are critically ill and those with central nervous system disease. Patients who cannot tolerate deoxycholate formulation of Amphotericin B can be given lipid formulations. Has excellent CNS penetration and is useful where there is CNS involvement after initial treatment with Amphotericin B.Prognosis Mortality rate in treated cases.

0-2% in treated cases among immunocompetent patients. 29% in immunocompromised patients. 40% in the subgroup of patients with AIDS. 68% in patients presenting as Epidemiology.

Distribution of blastomycosis in North America based on the map given by Kwon-Chung and Bennett, with modifications made according to case reports from a series of additional sources.Incidences in most endemic areas are circa 0.5 per 100,000 population, with occasional local areas attaining as high as 12 per 100,000. Most Canadian data fit this picture. In Ontario, Canada, considering both endemic and non-endemic areas, the overall incidence is around 0.3 cases per 100,000; northern Ontario, mostly endemic, has 2.44 per 100,000. Is calculated at 0.62 cases per 100,000. Remarkably higher incidences were shown for the region: 117 per 100,000 overall, with aboriginal reserve communities experiencing 404.9 per 100,000. In the United States, the incidence of blastomycosis is similarly high in hyperendemic areas.

For example, the city of Eagle River, Vilas County, Wisconsin, which has an incidence rate of 101.3 per 100,000; the county as a whole has been shown in two successive studies to have an incidence of ca. 40 cases per 100,000. An incidence of 277 per 100,000 was roughly calculated based on 9 cases seen in a Wisconsin aboriginal reservation during a time in which extensive excavation was done for new housing construction. The new case rates are greater in northern states such as, where from 1986 to 1995 there were 1.4 cases per 100,000 people.The study of outbreaks as well as trends in individual cases of blastomycosis has clarified a number of important matters.

Some of these relate to the ongoing effort to understand the source of infectious inoculum of this species, while others relate to which groups of people are especially likely to become infected. Human blastomycosis is primarily associated with forested areas and open watersheds; It primarily affects otherwise healthy, vigorous people, mostly middle-aged, who acquire the disease while working or undertaking recreational activities in sites conventionally considered clean, healthy and in many cases beautiful. Repeatedly associated activities include hunting, especially raccoon hunting, where accompanying dogs also tend to be affected, as well as working with wood or plant material in forested or riparian areas, involvement in forestry in highly endemic areas, excavation, fishing and possibly gardening and trapping. Urban infections There is also a developing profile of urban and other domestic blastomycosis cases, beginning with an outbreak tentatively attributed to construction dust in.

The city of, was also documented as a hyperendemic area based on incidence rates as high as 6.67 per 100,000 population for some areas of the city. Though proximity to open watersheds was linked to incidence in some areas, suggesting that outdoor activity within the city may be connected to many cases, there is also an increasing body of evidence that even the interiors of buildings may be risk areas. An early case concerned a prisoner who was confined to prison during the whole of his likely blastomycotic incubation period.

An epidemiological survey found that although many patients who contracted blastomycosis had engaged in fishing, hunting, gardening, outdoor work and excavation, the most strongly linked association in patients was living or visiting near waterways. Based on a similar finding in a Louisiana study, it has been suggested that place of residence might be the most important single factor in blastomycosis epidemiology in north central. Follow-up epidemiological and case studies indicated that clusters of cases were often associated with particular domiciles, often spread out over a period of years, and that there were uncommon but regularly occurring cases in which pets kept mostly or entirely indoors, in particular cats, contracted blastomycosis. The occurrence of blastomycosis, then, is an issue strongly linked to housing and domestic circumstances.Seasonal trends Seasonality and weather also appear to be linked to contraction of blastomycosis. Many studies have suggested an association between blastomycosis contraction and cool to moderately warm, moist periods of the spring and autumn or, in relatively warm winter areas. However, the entire summer or a known summer exposure date is included in the association in some studies. Occasional studies fail to detect a seasonal link.

In terms of weather, both unusually dry weather and unusually moist weather have been cited. The seemingly contradictory data can most likely be reconciled by proposing that B. Dermatitidis prospers in its natural habitats in times of moisture and moderate warmth, but that inoculum formed during these periods remains alive for some time and can be released into the air by subsequent dust formation under dry conditions.

Indeed, dust per se or construction potentially linked to dust has been associated with several outbreaks The data, then, tend to link blastomycosis to all weather, climate and atmospheric conditions except freezing weather, periods of snow cover, and extended periods of hot, dry summer weather in which soil is not agitated.Gender bias Sex is another factor inconstantly linked to contraction of blastomycosis: though many studies show more men than women affected, some show no sex-related bias. As mentioned above, most cases are in middle aged adults, but all age groups are affected, and cases in children are not uncommon.

Ethnic populations Ethnic group or race is frequently investigated in epidemiological studies of blastomycosis, but is potentially profoundly conflicted by differences in residence and in quality and accessibility of medical care, factors that have not been stringently controlled for to date. In the USA, a disproportionately high incidence and/or mortality rate is occasionally shown for blacks; whereas aboriginals in Canada are disproportionately linked to blastomycosis in some studies but not others. Incidence in aboriginal children may be unusually high. The Canadian data in some areas may be confounded or explained by the tendency to establish aboriginal communities in wooded, riparian, northern areas corresponding to the core habitat of B. Dermatitidis, often with known B.

Dermatitidis habitats such as woodpiles and beaver constructions in the near vicinity.Communicability There are a very small number of cases of human-to-human transmission of B. Dermatitidis related to dermal contact or sexual transmission of disseminated blastomycosis of the genital tract among spouses. History Blastomycosis was first described by Thomas Casper Gilchrist in 1894; because of this, it is sometimes called 'Gilchrist's disease'. It is also sometimes referred to as Chicago Disease. Other names for blastomycosis include North American blastomycosis, and blastomycetic dermatitis.Among a skeletal series of and later burial populations (the, 900-1673) found evidence for what may have been an epidemic of a serious spinal disease in adolescents and young adults. Several of the skeletons showed lesions in the spinal vertebrae in the lower back. There are two modern diseases that produce lesions in the bone similar to the ones Dr.

Buikstra found in these prehistoric specimens - and blastomycosis. The bony lesions in these two diseases are practically identical. Blastomycosis seems more probable as these young people in Late Woodland and Mississippian times may have been afflicted because they were spending more time cultivating plants than their Middle Woodland predecessors had done.

If true, it would be another severe penalty Late Woodland people had to pay as they shifted to agriculture as a way of life, and it would be a contributing factor to shortening their lifespans compared to those of the Middle Woodland people. Other animals Blastomycosis also affects an indefinitely broad range of mammalian hosts, and dogs in particular are a highly vulnerable sentinel species. The disease generally begins with acute respiratory symptoms and rapidly progresses to death.

Cats are the animals next most frequently detected as infected. Additional images. ^ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology.

Saunders Elsevier. From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019. From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019. ^ Murray P, Rosenthal K, Pfaller M (2015).

'Chapter 64: Systemic Mycoses Caused by Dimorphic Fungi'. Medical Microbiology (8 ed.). Pp. 629–633.

^. From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019. ^. From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019. ^.

From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019. From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019. Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH (March 2016).

Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 30 (1): 247–64.

From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019. ^ Crissey, John Thorne; Parish, Lawrence C.; Holubar, Karl (2002). Parthenon Publishing Group.

P. 86. ^ Kwon-Chung, K.J., Bennett, J.E.; Bennett, John E. Medical mycology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

^ Vasquez, JE; Mehta, JB; Agrawal, R; Sarubbi, FA (1998). 'Blastomycosis in northeast Tennessee'. 114 (2): 436–43. Veligandla SR, Hinrichs SH, Rupp ME, Lien EA, Neff JR, Iwen PC (October 2002). 118 (4): 536–41. Morgan, Matthew W; Salit, Irving E (1996). The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases.

7 (2): 147–151. ^ Crampton, TL; Light, RB; Berg, GM; Meyers, MP; Schroeder, GC; Hershfield, ES; Embil, JM (2002). 'Epidemiology and clinical spectrum of blastomycosis diagnosed at Manitoba hospitals'. Clinical Infectious Diseases.

34 (10): 1310–6. ^ Dwight, P.J.; Naus, M; Sarsfield, P; Limerick, B (2000). 'An outbreak of human blastomycosis: the epidemiology of blastomycosis in the Kenora catchment region of Ontario, Canada'. Canada Communicable Disease Report. 26 (10): 82–91. Kane, J; Righter, J; Krajden, S; Lester, RS (1983). Canadian Medical Association Journal.

129 (7): 728–31. Lester, RS; DeKoven, JG; Kane, J; Simor, AE; Krajden, S; Summerbell, RC (2000). CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 163 (10): 1309–12.

^ Morris, SK; Brophy, J; Richardson, SE; Summerbell, R; Parkin, PC; Jamieson, F; Limerick, B; Wiebe, L; Ford-Jones, EL (2006). Emerging Infectious Diseases.

12 (2): 274–9. Sekhon, AS; Jackson, FL; Jacobs, HJ (1982). 'Blastomycosis: report of the first case from Alberta Canada'. 79 (2): 65–9. Vallabh, V; Martin, T; Conly, JM (1988). The Western Journal of Medicine. 148 (4): 460–2.

Weapons A large assortment of killing tools., Creatures Hunt a wide variety of vicious beasts, Companions Your 'extra' friends during a hunt., Fun Events Participate and get great prizes!' Welcome to the Hunter Blade Wiki Hunter Blade is no longer an active game. Any additional comments or concerns about content are slightly moot. Lightbreak Blade is a Master Rank Great Sword Weapon in Monster Hunter World (MHW) Iceborne.All weapons have unique properties relating to their Attack Power, Elemental Damage and various different looks. Please see Weapon Mechanics to fully understand the depth of your Hunter Arsenal. Lightbreak Blade Information. Weapon from the Raging Brachydios Monster. Blade is a 1998 American superhero horror film directed by Stephen Norrington and written by David S. Goyer.Based on the Marvel Comics superhero of the same name, it is the first part of the Blade film series.The film stars Wesley Snipes in the title role with Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson and N'Bushe Wright in supporting roles. In the film, Blade is a Dhampir, a human with vampire. The Hunter's Blades Trilogy is a fantasy trilogy by American writer R.A. Salvatore.It follows the Paths of Darkness series and is composed of three books, The Thousand Orcs, The Lone Drow, and The Two Swords. The Two Swords was Salvatore's 17th work concerning one of his most famous characters, Drizzt Do'Urden.In this series, Drizzt takes a stand to stop the spread of chaos and war by an. Blade hunter wiki. Eric Brooks is a human-vampire hybrid who hunts vampires. Before he was born, his mother was attacked and bitten by a vampire, dying while giving birth to him. As he grew into puberty, he began exhibiting various vampire-like tendencies without their weaknesses. He was eventually found by Abraham Whistler, a vampire hunter who taught him to control his abilities and hunt vampires.

^ Rippon, John Willard (1988). Medical mycology: the pathogenic fungi and the pathogenic actinomycetes (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co. ^ Manetti, AC (1991). American Journal of Public Health.

81 (5): 633–6. ^ Cano, MV; Ponce-de-Leon, GF; Tippen, S; Lindsley, MD; Warwick, M; Hajjeh, RA (2003).

Epidemiology and Infection. 131 (2): 907–14. ^ Baumgardner, DJ; Brockman, K (1998). 'Epidemiology of human blastomycosis in Vilas County, Wisconsin. II: 1991-1996'. 97 (5): 44–7. Baumgardner, DJ; Egan, G; Giles, S; Laundre, B (2002).

'An outbreak of blastomycosis on a United States Indian reservation'. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine.

13 (4): 250–2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (1996). 'Blastomycosis-Wisconsin, 1986-1995'. 45 (28): 601–3.

DiSalvo, A.F. Al-Doory, Y.; DiSalvo, A.F. Ecology of Blastomyces dermatitidis. Pp. 43–73. Baumgardner, DJ; Steber, D; Glazier, R; Paretsky, DP; Egan, G; Baumgardner, AM; Prigge, D (2005).

'Geographic information system analysis of blastomycosis in northern Wisconsin, USA: waterways and soil'. Medical Mycology. 43 (2): 117–25. ^ Baumgardner, DJ; Knavel, EM; Steber, D; Swain, GR (2006). 'Geographic distribution of human blastomycosis cases in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA: association with urban watersheds'. 161 (5): 275–82.

^ Klein, Bruce S.; Vergeront, James M.; Weeks, Robert J.; Kumar, U. Nanda; Mathai, George; Varkey, Basil; Kaufman, Leo; Bradsher, Robert W.; Stoebig, James F.; Davis, Jeffrey P. 'Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in Soil Associated with a Large Outbreak of Blastomycosis in Wisconsin'. New England Journal of Medicine. 314 (9): 529–534. Armstrong, CW; Jenkins, SR; Kaufman, L; Kerkering, TM; Rouse, BS; Miller GB, Jr (1987). 'Common-source outbreak of blastomycosis in hunters and their dogs'.

The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 155 (3): 568–70. Kesselman, EW; Moore, S; Embil, JM (2005). 'Using local epidemiology to make a difficult diagnosis: a case of blastomycosis'. 7 (3): 171–3. Vaaler, AK; Bradsher, RW; Davies, SF (1990). 'Evidence of subclinical blastomycosis in forestry workers in northern Minnesota and northern Wisconsin'.

The American Journal of Medicine. 89 (4): 470–6.

^ Baumgardner, DJ; Buggy, BP; Mattson, BJ; Burdick, JS; Ludwig, D (1992). 'Epidemiology of blastomycosis in a region of high endemicity in north central Wisconsin'. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 15 (4): 629–35. ^ Kitchen, MS; Reiber, CD; Eastin, GB (1977).

'An urban epidemic of North American blastomycosis'. The American Review of Respiratory Disease. 115 (6): 1063–6.: (inactive 2020-03-08). Renston, JP; Morgan, J; DiMarco, AF (1992).

'Disseminated miliary blastomycosis leading to acute respiratory failure in an urban setting'. 101 (5): 1463–5. Lowry, PW; Kelso, KY; McFarland, LM (1989).

'Blastomycosis in Washington Parish, Louisiana, 1976-1985'. American Journal of Epidemiology. 130 (1): 151–9. ^ Blondin, N; Baumgardner, DJ; Moore, GE; Glickman, LT (2007). 'Blastomycosis in indoor cats: suburban Chicago, Illinois, USA'.

163 (2): 59–66. Baumgardner, DJ; Paretsky, DP (2001). 'Blastomycosis: more evidence for exposure near one's domicile'. 100 (7): 43–5. Rudmann, DG; Coolman, BR; Perez, CM; Glickman, LT (1992).

King & Assassins is a simple game in which deception and tension are paramount. One player takes the role of the the tyrant King and his soldiers. His objective is to push through the mob of angry citizens who have overrun the board. King and Assassins is an asymmetrical fantasy game of strategy and deception for two players. One player controls a vile king and his knightly lackeys who try to force their way into the castle through a mob of wrathful citizens. The other player controls the mob itself and – more importantly – three assassins who hide among the crowd hoping to kill or stop the ruler long enough for the. King and assassins board game. King & Assassins is a simple game in which deception and tension are paramount. One player takes the role of the the tyrant King and his soldiers. His objective is to push through the mob of angry citizens who have overrun the board and get back to safety behind his castle walls.

'Evaluation of risk factors for blastomycosis in dogs: 857 cases (1980-1990)'. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 201 (11): 1754–9. Arceneaux, KA; Taboada, J; Hosgood, G (1998). 'Blastomycosis in dogs: 115 cases (1980-1995)'. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

213 (5): 658–64. Archer, JR; Trainer, DO; Schell, RF (1987). 'Epidemiologic study of canine blastomycosis in Wisconsin'. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 190 (10): 1292–5. Chapman, SW; Lin, AC; Hendricks, KA; Nolan, RL; Currier, MM; Morris, KR; Turner, HR (1997).

'Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies'. Seminars in Respiratory Infections. 12 (3): 219–28. Proctor, ME; Klein, BS; Jones, JM; Davis, JP (2002). 'Cluster of pulmonary blastomycosis in a rural community: evidence for multiple high-risk environmental foci following a sustained period of diminished precipitation'. 153 (3): 113–20. De Groote, MA; Bjerke, R; Smith, H; Rhodes III, LV (2000).

'Expanding epidemiology of blastomycosis: clinical features and investigation of 2 cases in Colorado'. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 30 (3): 582–4. Baumgardner, DJ; Burdick, JS (1991).

'An outbreak of human and canine blastomycosis'. Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 13 (5): 898–905. Dworkin, MS; Duckro, AN; Proia, L; Semel, JD; Huhn, G (2005). 'The epidemiology of blastomycosis in Illinois and factors associated with death'. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 41 (12): e107–11.

Lemos, LB; Guo, M; Baliga, M (2000). 'Blastomycosis: organ involvement and etiologic diagnosis. A review of 123 patients from Mississippi'. Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 4 (6): 391–406.

Kepron, MW; Schoemperlen; Hershfield, ES; Zylak, CJ; Cherniack, RM (1972). Canadian Medical Association Journal. 106 (3): 243–6. Bachir, J; Fitch, GL (2006). 'Northern Wisconsin married couple infected with blastomycosis'. 105 (6): 55–7. Struever, Stuart and Felicia Antonelli Holton (1979).

Koster: Americans in Search of Their Prehistoric Past. New York: Anchor Press / Doubleday.Further reading. Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH (2016). Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 30 (1): 247–264. (Review).

McBride JA, Gauthier GM, Klein BS (2017). Clinics in Chest Medicine. 38 (3): 435–449.

(Review)External links Classification.

Blastomycosis is a potentially fatal fungal infection endemic to parts of North America. We used national multiple-cause-of-death data and census population estimates for 1990–2010 to calculate age-adjusted mortality rates and rate ratios (RRs). We modeled trends over time using Poisson regression. Death occurred more often among older persons (RR 2.11, 95% confidence limit CL 1.76, 2.53 for those 75–84 years of age vs.

55–64 years), men (RR 2.43, 95% CL 2.19, 2.70), Native Americans (RR 4.13, 95% CL 3.86, 4.42 vs. Whites), and blacks (RR 1.86, 95% CL 1.73, 2.01 vs. Whites), in notably younger persons of Asian origin (mean = 41.6 years vs. 64.2 years for whites); and in the South (RR 18.15, 95% CL 11.63, 28.34 vs. West) and Midwest (RR 23.10, 95% CL14.78, 36.12 vs. In regions where blastomycosis is endemic, we recommend that the diagnosis be considered in patients with pulmonary disease and that it be a reportable disease.

Blastomycosis is a systemic infection caused by the thermally dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis that can result in severe disease and death among humans and animals. Dermatitidis is endemic to the states bordering the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, the Great Lakes, and southern Canada; it is found in moist, acidic, enriched soil near wooded areas and in decaying vegetation or other organic material. Conidia, the spores, become airborne after disruption of areas contaminated with B. Infection occurs primarily through inhalation of the B.

Dermatitidis spores into the lungs, where they undergo transition to the invasive yeast phase. The infection can progress in the lung, where the infection may be limited, or it can disseminate and result in extrapulmonary disease, affecting other organ systems.The incubation period for blastomycosis is 3–15 weeks.

About 30%–50% of infections are asymptomatic. Pulmonary symptoms are the most common clinical manifestations; however, extrapulmonary disease can frequently manifest as cutaneous and skeletal disease and, less frequently, as genitourinary or central nervous system disease. Liver, spleen, pericardium, thyroid, gastrointestinal tract, or adrenal glands may also be involved. Misdiagnoses and delayed diagnoses are common because the signs and symptoms resemble those of other diseases, such as bacterial pneumonia, influenza, tuberculosis, other fungal infections, and some malignancies. Accurate diagnosis relies on a high index of suspicion with confirmation by using histologic examination, culture, antigen detection assays, or PCR tests.Antifungal agents, such as itraconazole for mild or moderate disease and amphotericin B for severe disease, can provide effective therapy, especially when administered early (,). With appropriate treatment, blastomycosis can be successfully treated without relapse; however, case-fatality rates of 4%–22% have been observed (,–). Although spontaneous recovery can occur (,), case-patients often require monitoring of clinical progress and administration of drugs on an inpatient basis.

Previous studies estimated average hospitalization costs for adults to be $20,000; that is likely less than the current true cost. Some reviews of outbreaks indicate a higher distribution of infection among persons of older age, male sex (,), black, Asian, and Native American racial/ethnic groups (,), and those who have outdoor occupations (,).

Both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts may experience disease and death (, –), although B. Dermatitidis disproportionately affects immunocompromised patients, who tend to have more rapid and extensive pulmonary involvement, extrapulmonary infection, complications, and higher mortality rates (25%–54%) (,–).Past studies have expanded the knowledge about blastomycosis through focusing on cases documented in specific immunocompromised persons and statewide occurrences or in areas in which the disease is endemic (,–,–); however, such studies may be limited for making definitive conclusions by their scope and small sample size. Much remains unknown about the public health burden of blastomycosis-related deaths in the United States. Reports suggest an increase in the number of blastomycosis cases in recent years (,).

Clearer identification of risk factors from national data may raise awareness of blastomycosis in the United States and support adding it to the list of reportable diseases in regions where the pathogen is endemic to improve surveillance and control. In this study, we assessed the public health burden of blastomycosis-related deaths by examining US mortality-associated data and evaluating demographic, temporal, and geographic associations as potential risk factors. AnalysisTo ensure more stable estimates, we aggregated data for the study period.

We calculated mortality rates and rate ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence limits (CLs) by age, sex, race/ethnicity, geographic region, and year of death using a maximum likelihood analysis presuming the response variable had a Poisson distribution , and with bridged-race population estimates data and designated geographic boundaries from the US census. We computed age-adjusted mortality rates using adjustment weights from the year 2000 US standard population data. We assessed temporal trends in age-adjusted mortality rates using a Poisson regression model of deaths per person-years in the population, designating year and age group dummy variables as independent variables, and the population as the offset.

We calculated the percentage change by year based on the estimated slope parameter and examined the Poisson regression models for overdispersion. We performed all analyses using SAS for Windows version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

ResultsWe identified 1,216 blastomycosis-related deaths among 49,574,649 deaths in the United States during 1990–2010. Among those 1,216 deaths, blastomycosis was reported as the underlying cause of death for 741 (60.9%), and as a contributing cause of death for 475 (39.1%).

The overall age-adjusted mortality rate for the period was 0.21 (95% CL 0.20, 0.22) per 1 million person-years. Using Poisson regression, we identified a 2.21% (95% CL −3.11, −1.29) decline in blastomycosis-related mortality rates during the period. AgeThe mean age at death from blastomycosis was 60.8 years. Using 75 as the average age at death (,), we calculated that 19,097 years of potential life were lost.

The mortality rates associated with blastomycosis increased with increasing age, peaking in the 75- to 84-year age group. The mean age at death from blastomycosis was significantly lower among Hispanics (p. (%) deathsMean age at death, yAge-adjusted mortality rate/1 million person-years (95% CL)†Age-adjusted mortality rate ratio (95% CL)SexF409 (33.6)62.30.14 (0.13, 0.16)1M807 (66.4)60.10.35 (0.32, 0.37)2.43 (2.19, 2.70)Race/ethnicityWhite918 (75.5)64.20.22 (0.21, 0.23)1Hispanic25 (2.1)53.00.06 (0.03, 0.08)0.25 (0.19, 0.33)Black223 (18.3)50.60.41 (0.35, 0.46)1.86 (1.73, 2.01)Asian20 (1.6)41.60.11 (0.06, 0.15)0.47 (0.41, 0.55)Native American30 (2.5)52.90.91 (0.57, 1.25)4.13 (3.86, 4.42)Age, y‡. Geographic RegionMost (96.7%) of the blastomycosis-related deaths occurred in the southern and midwestern regions, and a small proportion of deaths occurred in the northeastern and western regions.

The midwestern region had the highest mortality rate, followed by the southern, northeastern, and western regions. Percentage changes in mortality rates per year over the period, calculated by using Poisson regression, showed an increase in mortality rates in the midwestern region, and a decline in the southern region.shows the results of a subanalysis of the demographic characteristics of populations in the southern and midwestern regions. In the southern region, the mean age at death from blastomycosis was significantly lower among Native Americans (p = 0.03), blacks (p. (%) deathsMean age at death, yAge-adjusted mortality rate per 1 million person-years (95% CL)No. DiscussionOur findings indicate that blastomycosis is a noteworthy cause of preventable death in the United States. These findings confirm the demographic risk factors of blastomycosis indicated in previous case reports and extend these to mortality rates.

Blastomycosis death occurred more often among older persons than among younger persons , and more often among men than women (,). The age association found likely represents waning age-related immune function and higher prevalence of immunocompromising conditions. The observed sex differences in blastomycosis mortality may be attributable to differences in occupational or recreational exposures that increase risk for infection. For example, those who work outdoors involving construction, excavation, or forestry, or participate in outdoor recreational activities such as hunting (,), may more likely be exposed than those who principally work indoors.The disproportionate burden of blastomycosis deaths sustained by persons of Native American or black race is also consistent with previous reports (,). Increased exposure and prevalence of infection, reduced access to health care, and genetic differences may play a role in the observed race-specific disparities in blastomycosis mortality rates.

A finding of the current study is that even though persons of Asian descent are at lower risk for dying from blastomycosis than whites, those who died from blastomycosis did so at a much younger age (22.6 years younger). This disparity is even greater in the midwestern region, where Asians died at an age 27.2 years younger than did whites.Consistent with the recognized geographic distribution of B. Dermatitidis (,), we found that death related to blastomycosis occurred more often among persons who resided in the midwestern or southern regions than among those in the western and northeastern regions. During the study period, the southern region showed decreases in mortality rates, and the midwestern region, which had the highest mortality rate, showed an increase in rate.The use of population-based data and large numbers can provide insight, though some limitations associated with using MCOD data should be considered.

First, potential underdiagnosis and underreporting of death related to blastomycosis may lead to underestimates of mortality rates and the true public health burden of blastomycosis in the United States. Low physician awareness of blastomycosis may be a contributor. Second, it was not possible to verify accuracy of recorded data or access supplemental data. For example, there may be reporting errors regarding correct race/ethnicity identification on death certificates and in population census reports. Third, we could not adjust for other possible confounders (i.e., smoking, socioeconomic factors, activity, lifestyle, occupation) because these data are not recorded on death certificates. These limitations must be considered along with our findings.This study sheds light on the scope of the incidence of blastomycosis in the United States, though the true incidence may be greater than that reported here.

Dermatitidis infection may be difficult to prevent because of its widespread distribution in areas where blastomycosis is endemic, deaths resulting from blastomycosis can be prevented with early recognition and treatment of patients with symptomatic infection. The continued incidence of blastomycosis in the United States, as indicated by the observed modest decrease in the mortality rates over the 21-year study period, calls for improvement in provider and community awareness, which may lead to including blastomycosis as a diagnostic consideration in patients with pulmonary disease refractory to treatment. Our findings, recent reports of disproportionately high infection rates among Asians , and the lack of decline in the mortality rates in the midwestern region support further investigation.

We also encourage improvements in blastomycosis surveillance that involve examining trends in incident cases, hospitalization (including length of stay), timely diagnosis, and treatment to further elucidate the burden of blastomycosis in the United States.

Popular Posts

Not to be confused with \'South American blastomycosis\'. BlastomycosisOther namesNorth American blastomycosisSkin lesions of blastomycosis.Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by inhaling spores. If it involves only the lungs, it is called pulmonary blastomycosis.

Blastomycosis infections are most common in dogs between 1 and 5. Humans have to contract the fungal disease the same way as dogs:. Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic to areas. A relationship between canine blastomycosis and human disease.

Only about half of people with the disease have symptoms, which can include, weight loss, chest pain,. These symptoms usually develop between three weeks and three months after breathing in the spores.

In those with, the disease can spread to other areas of the body, including the skin and bones.Blastomyces dermatitis is found in the soil and decaying organic matter like wood or leaves. Participating in outdoor activities like hunting or camping in wooded areas increases the risk of developing blastomycosis. There is no vaccine, but the disease can be prevented by not disturbing the soil. Treatment is with for mild or moderate disease and for severe disease. With both, the duration of treatment is 6–12 months. Overall, 4-6% of people who develop blastomycosis die; however, if the central nervous system is involved, this rises to 18%.

People with or on have the highest risk of death at 25-40%.Blastomycosis is to the eastern United States, especially the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, the Great Lakes, and the St. Lawrence River.

It is also endemic to some parts of Canada, including Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba. In these areas, there are about 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 per year.

Blastomycosis was first described by Thomas Casper Gilchrist in 1894; because of this, it is sometimes called \'Gilchrist\'s disease\'. Large, broadly-based budding yeast cells characteristic of Blastomyces dermatitidis in a GMS-stained biopsy section from a human leg.Inhaled conidia of B. Dermatitidis are by neutrophils and macrophages in alveoli. Some of these escape phagocytosis and transform into yeast phase rapidly. Having thick walls, these are resistant to phagocytosis and express glycoprotein, BAD-1, which is a virulence factor as well as an epitope.

In lung tissue, they multiply and may disseminate through blood and to other organs, including the skin, bone, genitourinary tract, and brain. The incubation period is 30 to 100 days, although infection can be asymptomatic. Diagnosis Once suspected, the diagnosis of blastomycosis can usually be confirmed by demonstration of the characteristic broad based budding organisms in sputum or tissues by KOH prep, cytology, or histology.

Tissue biopsy of skin or other organs may be required in order to diagnose extra-pulmonary disease. Blastomycosis is histologically associated with granulomatous nodules. Commercially available urine antigen testing appears to be quite sensitive in suggesting the diagnosis in cases where the organism is not readily detected. While culture of the organism remains the definitive diagnostic standard, its slow growing nature can lead to delays in treatment of up to several weeks. However, sometimes blood and sputum cultures may not detect blastomycosis. Treatment given orally is the treatment of choice for most forms of the disease.

May also be used. Cure rates are high, and the treatment over a period of months is usually well tolerated.

Is considerably more toxic, and is usually reserved for immunocompromised patients who are critically ill and those with central nervous system disease. Patients who cannot tolerate deoxycholate formulation of Amphotericin B can be given lipid formulations. Has excellent CNS penetration and is useful where there is CNS involvement after initial treatment with Amphotericin B.Prognosis Mortality rate in treated cases.

0-2% in treated cases among immunocompetent patients. 29% in immunocompromised patients. 40% in the subgroup of patients with AIDS. 68% in patients presenting as Epidemiology.

Distribution of blastomycosis in North America based on the map given by Kwon-Chung and Bennett, with modifications made according to case reports from a series of additional sources.Incidences in most endemic areas are circa 0.5 per 100,000 population, with occasional local areas attaining as high as 12 per 100,000. Most Canadian data fit this picture. In Ontario, Canada, considering both endemic and non-endemic areas, the overall incidence is around 0.3 cases per 100,000; northern Ontario, mostly endemic, has 2.44 per 100,000. Is calculated at 0.62 cases per 100,000. Remarkably higher incidences were shown for the region: 117 per 100,000 overall, with aboriginal reserve communities experiencing 404.9 per 100,000. In the United States, the incidence of blastomycosis is similarly high in hyperendemic areas.

For example, the city of Eagle River, Vilas County, Wisconsin, which has an incidence rate of 101.3 per 100,000; the county as a whole has been shown in two successive studies to have an incidence of ca. 40 cases per 100,000. An incidence of 277 per 100,000 was roughly calculated based on 9 cases seen in a Wisconsin aboriginal reservation during a time in which extensive excavation was done for new housing construction. The new case rates are greater in northern states such as, where from 1986 to 1995 there were 1.4 cases per 100,000 people.The study of outbreaks as well as trends in individual cases of blastomycosis has clarified a number of important matters.

Some of these relate to the ongoing effort to understand the source of infectious inoculum of this species, while others relate to which groups of people are especially likely to become infected. Human blastomycosis is primarily associated with forested areas and open watersheds; It primarily affects otherwise healthy, vigorous people, mostly middle-aged, who acquire the disease while working or undertaking recreational activities in sites conventionally considered clean, healthy and in many cases beautiful. Repeatedly associated activities include hunting, especially raccoon hunting, where accompanying dogs also tend to be affected, as well as working with wood or plant material in forested or riparian areas, involvement in forestry in highly endemic areas, excavation, fishing and possibly gardening and trapping. Urban infections There is also a developing profile of urban and other domestic blastomycosis cases, beginning with an outbreak tentatively attributed to construction dust in.

The city of, was also documented as a hyperendemic area based on incidence rates as high as 6.67 per 100,000 population for some areas of the city. Though proximity to open watersheds was linked to incidence in some areas, suggesting that outdoor activity within the city may be connected to many cases, there is also an increasing body of evidence that even the interiors of buildings may be risk areas. An early case concerned a prisoner who was confined to prison during the whole of his likely blastomycotic incubation period.

An epidemiological survey found that although many patients who contracted blastomycosis had engaged in fishing, hunting, gardening, outdoor work and excavation, the most strongly linked association in patients was living or visiting near waterways. Based on a similar finding in a Louisiana study, it has been suggested that place of residence might be the most important single factor in blastomycosis epidemiology in north central. Follow-up epidemiological and case studies indicated that clusters of cases were often associated with particular domiciles, often spread out over a period of years, and that there were uncommon but regularly occurring cases in which pets kept mostly or entirely indoors, in particular cats, contracted blastomycosis. The occurrence of blastomycosis, then, is an issue strongly linked to housing and domestic circumstances.Seasonal trends Seasonality and weather also appear to be linked to contraction of blastomycosis. Many studies have suggested an association between blastomycosis contraction and cool to moderately warm, moist periods of the spring and autumn or, in relatively warm winter areas. However, the entire summer or a known summer exposure date is included in the association in some studies. Occasional studies fail to detect a seasonal link.

In terms of weather, both unusually dry weather and unusually moist weather have been cited. The seemingly contradictory data can most likely be reconciled by proposing that B. Dermatitidis prospers in its natural habitats in times of moisture and moderate warmth, but that inoculum formed during these periods remains alive for some time and can be released into the air by subsequent dust formation under dry conditions.

Indeed, dust per se or construction potentially linked to dust has been associated with several outbreaks The data, then, tend to link blastomycosis to all weather, climate and atmospheric conditions except freezing weather, periods of snow cover, and extended periods of hot, dry summer weather in which soil is not agitated.Gender bias Sex is another factor inconstantly linked to contraction of blastomycosis: though many studies show more men than women affected, some show no sex-related bias. As mentioned above, most cases are in middle aged adults, but all age groups are affected, and cases in children are not uncommon.

Ethnic populations Ethnic group or race is frequently investigated in epidemiological studies of blastomycosis, but is potentially profoundly conflicted by differences in residence and in quality and accessibility of medical care, factors that have not been stringently controlled for to date. In the USA, a disproportionately high incidence and/or mortality rate is occasionally shown for blacks; whereas aboriginals in Canada are disproportionately linked to blastomycosis in some studies but not others. Incidence in aboriginal children may be unusually high. The Canadian data in some areas may be confounded or explained by the tendency to establish aboriginal communities in wooded, riparian, northern areas corresponding to the core habitat of B. Dermatitidis, often with known B.

Dermatitidis habitats such as woodpiles and beaver constructions in the near vicinity.Communicability There are a very small number of cases of human-to-human transmission of B. Dermatitidis related to dermal contact or sexual transmission of disseminated blastomycosis of the genital tract among spouses. History Blastomycosis was first described by Thomas Casper Gilchrist in 1894; because of this, it is sometimes called \'Gilchrist\'s disease\'. It is also sometimes referred to as Chicago Disease. Other names for blastomycosis include North American blastomycosis, and blastomycetic dermatitis.Among a skeletal series of and later burial populations (the, 900-1673) found evidence for what may have been an epidemic of a serious spinal disease in adolescents and young adults. Several of the skeletons showed lesions in the spinal vertebrae in the lower back. There are two modern diseases that produce lesions in the bone similar to the ones Dr.

Buikstra found in these prehistoric specimens - and blastomycosis. The bony lesions in these two diseases are practically identical. Blastomycosis seems more probable as these young people in Late Woodland and Mississippian times may have been afflicted because they were spending more time cultivating plants than their Middle Woodland predecessors had done.

If true, it would be another severe penalty Late Woodland people had to pay as they shifted to agriculture as a way of life, and it would be a contributing factor to shortening their lifespans compared to those of the Middle Woodland people. Other animals Blastomycosis also affects an indefinitely broad range of mammalian hosts, and dogs in particular are a highly vulnerable sentinel species. The disease generally begins with acute respiratory symptoms and rapidly progresses to death.

Cats are the animals next most frequently detected as infected. Additional images. ^ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. Andrews\' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology.

Saunders Elsevier. From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019. From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019. ^ Murray P, Rosenthal K, Pfaller M (2015).

\'Chapter 64: Systemic Mycoses Caused by Dimorphic Fungi\'. Medical Microbiology (8 ed.). Pp. 629–633.

^. From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019. ^. From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019. ^.

From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019. From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019. Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH (March 2016).

Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 30 (1): 247–64.

From the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019. ^ Crissey, John Thorne; Parish, Lawrence C.; Holubar, Karl (2002). Parthenon Publishing Group.

P. 86. ^ Kwon-Chung, K.J., Bennett, J.E.; Bennett, John E. Medical mycology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

^ Vasquez, JE; Mehta, JB; Agrawal, R; Sarubbi, FA (1998). \'Blastomycosis in northeast Tennessee\'. 114 (2): 436–43. Veligandla SR, Hinrichs SH, Rupp ME, Lien EA, Neff JR, Iwen PC (October 2002). 118 (4): 536–41. Morgan, Matthew W; Salit, Irving E (1996). The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases.

7 (2): 147–151. ^ Crampton, TL; Light, RB; Berg, GM; Meyers, MP; Schroeder, GC; Hershfield, ES; Embil, JM (2002). \'Epidemiology and clinical spectrum of blastomycosis diagnosed at Manitoba hospitals\'. Clinical Infectious Diseases.

34 (10): 1310–6. ^ Dwight, P.J.; Naus, M; Sarsfield, P; Limerick, B (2000). \'An outbreak of human blastomycosis: the epidemiology of blastomycosis in the Kenora catchment region of Ontario, Canada\'. Canada Communicable Disease Report. 26 (10): 82–91. Kane, J; Righter, J; Krajden, S; Lester, RS (1983). Canadian Medical Association Journal.

129 (7): 728–31. Lester, RS; DeKoven, JG; Kane, J; Simor, AE; Krajden, S; Summerbell, RC (2000). CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 163 (10): 1309–12.

^ Morris, SK; Brophy, J; Richardson, SE; Summerbell, R; Parkin, PC; Jamieson, F; Limerick, B; Wiebe, L; Ford-Jones, EL (2006). Emerging Infectious Diseases.

12 (2): 274–9. Sekhon, AS; Jackson, FL; Jacobs, HJ (1982). \'Blastomycosis: report of the first case from Alberta Canada\'. 79 (2): 65–9. Vallabh, V; Martin, T; Conly, JM (1988). The Western Journal of Medicine. 148 (4): 460–2.

Weapons A large assortment of killing tools., Creatures Hunt a wide variety of vicious beasts, Companions Your \'extra\' friends during a hunt., Fun Events Participate and get great prizes!\' Welcome to the Hunter Blade Wiki Hunter Blade is no longer an active game. Any additional comments or concerns about content are slightly moot. Lightbreak Blade is a Master Rank Great Sword Weapon in Monster Hunter World (MHW) Iceborne.All weapons have unique properties relating to their Attack Power, Elemental Damage and various different looks. Please see Weapon Mechanics to fully understand the depth of your Hunter Arsenal. Lightbreak Blade Information. Weapon from the Raging Brachydios Monster. Blade is a 1998 American superhero horror film directed by Stephen Norrington and written by David S. Goyer.Based on the Marvel Comics superhero of the same name, it is the first part of the Blade film series.The film stars Wesley Snipes in the title role with Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson and N\'Bushe Wright in supporting roles. In the film, Blade is a Dhampir, a human with vampire. The Hunter\'s Blades Trilogy is a fantasy trilogy by American writer R.A. Salvatore.It follows the Paths of Darkness series and is composed of three books, The Thousand Orcs, The Lone Drow, and The Two Swords. The Two Swords was Salvatore\'s 17th work concerning one of his most famous characters, Drizzt Do\'Urden.In this series, Drizzt takes a stand to stop the spread of chaos and war by an. Blade hunter wiki. Eric Brooks is a human-vampire hybrid who hunts vampires. Before he was born, his mother was attacked and bitten by a vampire, dying while giving birth to him. As he grew into puberty, he began exhibiting various vampire-like tendencies without their weaknesses. He was eventually found by Abraham Whistler, a vampire hunter who taught him to control his abilities and hunt vampires.

^ Rippon, John Willard (1988). Medical mycology: the pathogenic fungi and the pathogenic actinomycetes (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co. ^ Manetti, AC (1991). American Journal of Public Health.

81 (5): 633–6. ^ Cano, MV; Ponce-de-Leon, GF; Tippen, S; Lindsley, MD; Warwick, M; Hajjeh, RA (2003).

Epidemiology and Infection. 131 (2): 907–14. ^ Baumgardner, DJ; Brockman, K (1998). \'Epidemiology of human blastomycosis in Vilas County, Wisconsin. II: 1991-1996\'. 97 (5): 44–7. Baumgardner, DJ; Egan, G; Giles, S; Laundre, B (2002).

\'An outbreak of blastomycosis on a United States Indian reservation\'. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine.

13 (4): 250–2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (1996). \'Blastomycosis-Wisconsin, 1986-1995\'. 45 (28): 601–3.

DiSalvo, A.F. Al-Doory, Y.; DiSalvo, A.F. Ecology of Blastomyces dermatitidis. Pp. 43–73. Baumgardner, DJ; Steber, D; Glazier, R; Paretsky, DP; Egan, G; Baumgardner, AM; Prigge, D (2005).

\'Geographic information system analysis of blastomycosis in northern Wisconsin, USA: waterways and soil\'. Medical Mycology. 43 (2): 117–25. ^ Baumgardner, DJ; Knavel, EM; Steber, D; Swain, GR (2006). \'Geographic distribution of human blastomycosis cases in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA: association with urban watersheds\'. 161 (5): 275–82.

^ Klein, Bruce S.; Vergeront, James M.; Weeks, Robert J.; Kumar, U. Nanda; Mathai, George; Varkey, Basil; Kaufman, Leo; Bradsher, Robert W.; Stoebig, James F.; Davis, Jeffrey P. \'Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in Soil Associated with a Large Outbreak of Blastomycosis in Wisconsin\'. New England Journal of Medicine. 314 (9): 529–534. Armstrong, CW; Jenkins, SR; Kaufman, L; Kerkering, TM; Rouse, BS; Miller GB, Jr (1987). \'Common-source outbreak of blastomycosis in hunters and their dogs\'.

The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 155 (3): 568–70. Kesselman, EW; Moore, S; Embil, JM (2005). \'Using local epidemiology to make a difficult diagnosis: a case of blastomycosis\'. 7 (3): 171–3. Vaaler, AK; Bradsher, RW; Davies, SF (1990). \'Evidence of subclinical blastomycosis in forestry workers in northern Minnesota and northern Wisconsin\'.

The American Journal of Medicine. 89 (4): 470–6.

^ Baumgardner, DJ; Buggy, BP; Mattson, BJ; Burdick, JS; Ludwig, D (1992). \'Epidemiology of blastomycosis in a region of high endemicity in north central Wisconsin\'. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 15 (4): 629–35. ^ Kitchen, MS; Reiber, CD; Eastin, GB (1977).

\'An urban epidemic of North American blastomycosis\'. The American Review of Respiratory Disease. 115 (6): 1063–6.: (inactive 2020-03-08). Renston, JP; Morgan, J; DiMarco, AF (1992).

\'Disseminated miliary blastomycosis leading to acute respiratory failure in an urban setting\'. 101 (5): 1463–5. Lowry, PW; Kelso, KY; McFarland, LM (1989).

\'Blastomycosis in Washington Parish, Louisiana, 1976-1985\'. American Journal of Epidemiology. 130 (1): 151–9. ^ Blondin, N; Baumgardner, DJ; Moore, GE; Glickman, LT (2007). \'Blastomycosis in indoor cats: suburban Chicago, Illinois, USA\'.

163 (2): 59–66. Baumgardner, DJ; Paretsky, DP (2001). \'Blastomycosis: more evidence for exposure near one\'s domicile\'. 100 (7): 43–5. Rudmann, DG; Coolman, BR; Perez, CM; Glickman, LT (1992).

King & Assassins is a simple game in which deception and tension are paramount. One player takes the role of the the tyrant King and his soldiers. His objective is to push through the mob of angry citizens who have overrun the board. King and Assassins is an asymmetrical fantasy game of strategy and deception for two players. One player controls a vile king and his knightly lackeys who try to force their way into the castle through a mob of wrathful citizens. The other player controls the mob itself and – more importantly – three assassins who hide among the crowd hoping to kill or stop the ruler long enough for the. King and assassins board game. King & Assassins is a simple game in which deception and tension are paramount. One player takes the role of the the tyrant King and his soldiers. His objective is to push through the mob of angry citizens who have overrun the board and get back to safety behind his castle walls.

\'Evaluation of risk factors for blastomycosis in dogs: 857 cases (1980-1990)\'. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 201 (11): 1754–9. Arceneaux, KA; Taboada, J; Hosgood, G (1998). \'Blastomycosis in dogs: 115 cases (1980-1995)\'. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

213 (5): 658–64. Archer, JR; Trainer, DO; Schell, RF (1987). \'Epidemiologic study of canine blastomycosis in Wisconsin\'. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 190 (10): 1292–5. Chapman, SW; Lin, AC; Hendricks, KA; Nolan, RL; Currier, MM; Morris, KR; Turner, HR (1997).

\'Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies\'. Seminars in Respiratory Infections. 12 (3): 219–28. Proctor, ME; Klein, BS; Jones, JM; Davis, JP (2002). \'Cluster of pulmonary blastomycosis in a rural community: evidence for multiple high-risk environmental foci following a sustained period of diminished precipitation\'. 153 (3): 113–20. De Groote, MA; Bjerke, R; Smith, H; Rhodes III, LV (2000).

\'Expanding epidemiology of blastomycosis: clinical features and investigation of 2 cases in Colorado\'. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 30 (3): 582–4. Baumgardner, DJ; Burdick, JS (1991).

\'An outbreak of human and canine blastomycosis\'. Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 13 (5): 898–905. Dworkin, MS; Duckro, AN; Proia, L; Semel, JD; Huhn, G (2005). \'The epidemiology of blastomycosis in Illinois and factors associated with death\'. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 41 (12): e107–11.

Lemos, LB; Guo, M; Baliga, M (2000). \'Blastomycosis: organ involvement and etiologic diagnosis. A review of 123 patients from Mississippi\'. Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 4 (6): 391–406.

Kepron, MW; Schoemperlen; Hershfield, ES; Zylak, CJ; Cherniack, RM (1972). Canadian Medical Association Journal. 106 (3): 243–6. Bachir, J; Fitch, GL (2006). \'Northern Wisconsin married couple infected with blastomycosis\'. 105 (6): 55–7. Struever, Stuart and Felicia Antonelli Holton (1979).

Koster: Americans in Search of Their Prehistoric Past. New York: Anchor Press / Doubleday.Further reading. Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH (2016). Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 30 (1): 247–264. (Review).

McBride JA, Gauthier GM, Klein BS (2017). Clinics in Chest Medicine. 38 (3): 435–449.

(Review)External links Classification.

Blastomycosis is a potentially fatal fungal infection endemic to parts of North America. We used national multiple-cause-of-death data and census population estimates for 1990–2010 to calculate age-adjusted mortality rates and rate ratios (RRs). We modeled trends over time using Poisson regression. Death occurred more often among older persons (RR 2.11, 95% confidence limit CL 1.76, 2.53 for those 75–84 years of age vs.

55–64 years), men (RR 2.43, 95% CL 2.19, 2.70), Native Americans (RR 4.13, 95% CL 3.86, 4.42 vs. Whites), and blacks (RR 1.86, 95% CL 1.73, 2.01 vs. Whites), in notably younger persons of Asian origin (mean = 41.6 years vs. 64.2 years for whites); and in the South (RR 18.15, 95% CL 11.63, 28.34 vs. West) and Midwest (RR 23.10, 95% CL14.78, 36.12 vs. In regions where blastomycosis is endemic, we recommend that the diagnosis be considered in patients with pulmonary disease and that it be a reportable disease.

Blastomycosis is a systemic infection caused by the thermally dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis that can result in severe disease and death among humans and animals. Dermatitidis is endemic to the states bordering the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, the Great Lakes, and southern Canada; it is found in moist, acidic, enriched soil near wooded areas and in decaying vegetation or other organic material. Conidia, the spores, become airborne after disruption of areas contaminated with B. Infection occurs primarily through inhalation of the B.

Dermatitidis spores into the lungs, where they undergo transition to the invasive yeast phase. The infection can progress in the lung, where the infection may be limited, or it can disseminate and result in extrapulmonary disease, affecting other organ systems.The incubation period for blastomycosis is 3–15 weeks.

About 30%–50% of infections are asymptomatic. Pulmonary symptoms are the most common clinical manifestations; however, extrapulmonary disease can frequently manifest as cutaneous and skeletal disease and, less frequently, as genitourinary or central nervous system disease. Liver, spleen, pericardium, thyroid, gastrointestinal tract, or adrenal glands may also be involved. Misdiagnoses and delayed diagnoses are common because the signs and symptoms resemble those of other diseases, such as bacterial pneumonia, influenza, tuberculosis, other fungal infections, and some malignancies. Accurate diagnosis relies on a high index of suspicion with confirmation by using histologic examination, culture, antigen detection assays, or PCR tests.Antifungal agents, such as itraconazole for mild or moderate disease and amphotericin B for severe disease, can provide effective therapy, especially when administered early (,). With appropriate treatment, blastomycosis can be successfully treated without relapse; however, case-fatality rates of 4%–22% have been observed (,–). Although spontaneous recovery can occur (,), case-patients often require monitoring of clinical progress and administration of drugs on an inpatient basis.

Previous studies estimated average hospitalization costs for adults to be $20,000; that is likely less than the current true cost. Some reviews of outbreaks indicate a higher distribution of infection among persons of older age, male sex (,), black, Asian, and Native American racial/ethnic groups (,), and those who have outdoor occupations (,).

Both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts may experience disease and death (, –), although B. Dermatitidis disproportionately affects immunocompromised patients, who tend to have more rapid and extensive pulmonary involvement, extrapulmonary infection, complications, and higher mortality rates (25%–54%) (,–).Past studies have expanded the knowledge about blastomycosis through focusing on cases documented in specific immunocompromised persons and statewide occurrences or in areas in which the disease is endemic (,–,–); however, such studies may be limited for making definitive conclusions by their scope and small sample size. Much remains unknown about the public health burden of blastomycosis-related deaths in the United States. Reports suggest an increase in the number of blastomycosis cases in recent years (,).

Clearer identification of risk factors from national data may raise awareness of blastomycosis in the United States and support adding it to the list of reportable diseases in regions where the pathogen is endemic to improve surveillance and control. In this study, we assessed the public health burden of blastomycosis-related deaths by examining US mortality-associated data and evaluating demographic, temporal, and geographic associations as potential risk factors. AnalysisTo ensure more stable estimates, we aggregated data for the study period.

We calculated mortality rates and rate ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence limits (CLs) by age, sex, race/ethnicity, geographic region, and year of death using a maximum likelihood analysis presuming the response variable had a Poisson distribution , and with bridged-race population estimates data and designated geographic boundaries from the US census. We computed age-adjusted mortality rates using adjustment weights from the year 2000 US standard population data. We assessed temporal trends in age-adjusted mortality rates using a Poisson regression model of deaths per person-years in the population, designating year and age group dummy variables as independent variables, and the population as the offset.

We calculated the percentage change by year based on the estimated slope parameter and examined the Poisson regression models for overdispersion. We performed all analyses using SAS for Windows version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

ResultsWe identified 1,216 blastomycosis-related deaths among 49,574,649 deaths in the United States during 1990–2010. Among those 1,216 deaths, blastomycosis was reported as the underlying cause of death for 741 (60.9%), and as a contributing cause of death for 475 (39.1%).

The overall age-adjusted mortality rate for the period was 0.21 (95% CL 0.20, 0.22) per 1 million person-years. Using Poisson regression, we identified a 2.21% (95% CL −3.11, −1.29) decline in blastomycosis-related mortality rates during the period. AgeThe mean age at death from blastomycosis was 60.8 years. Using 75 as the average age at death (,), we calculated that 19,097 years of potential life were lost.

The mortality rates associated with blastomycosis increased with increasing age, peaking in the 75- to 84-year age group. The mean age at death from blastomycosis was significantly lower among Hispanics (p. (%) deathsMean age at death, yAge-adjusted mortality rate/1 million person-years (95% CL)†Age-adjusted mortality rate ratio (95% CL)SexF409 (33.6)62.30.14 (0.13, 0.16)1M807 (66.4)60.10.35 (0.32, 0.37)2.43 (2.19, 2.70)Race/ethnicityWhite918 (75.5)64.20.22 (0.21, 0.23)1Hispanic25 (2.1)53.00.06 (0.03, 0.08)0.25 (0.19, 0.33)Black223 (18.3)50.60.41 (0.35, 0.46)1.86 (1.73, 2.01)Asian20 (1.6)41.60.11 (0.06, 0.15)0.47 (0.41, 0.55)Native American30 (2.5)52.90.91 (0.57, 1.25)4.13 (3.86, 4.42)Age, y‡. Geographic RegionMost (96.7%) of the blastomycosis-related deaths occurred in the southern and midwestern regions, and a small proportion of deaths occurred in the northeastern and western regions.

The midwestern region had the highest mortality rate, followed by the southern, northeastern, and western regions. Percentage changes in mortality rates per year over the period, calculated by using Poisson regression, showed an increase in mortality rates in the midwestern region, and a decline in the southern region.shows the results of a subanalysis of the demographic characteristics of populations in the southern and midwestern regions. In the southern region, the mean age at death from blastomycosis was significantly lower among Native Americans (p = 0.03), blacks (p. (%) deathsMean age at death, yAge-adjusted mortality rate per 1 million person-years (95% CL)No. DiscussionOur findings indicate that blastomycosis is a noteworthy cause of preventable death in the United States. These findings confirm the demographic risk factors of blastomycosis indicated in previous case reports and extend these to mortality rates.

Blastomycosis death occurred more often among older persons than among younger persons , and more often among men than women (,). The age association found likely represents waning age-related immune function and higher prevalence of immunocompromising conditions. The observed sex differences in blastomycosis mortality may be attributable to differences in occupational or recreational exposures that increase risk for infection. For example, those who work outdoors involving construction, excavation, or forestry, or participate in outdoor recreational activities such as hunting (,), may more likely be exposed than those who principally work indoors.The disproportionate burden of blastomycosis deaths sustained by persons of Native American or black race is also consistent with previous reports (,). Increased exposure and prevalence of infection, reduced access to health care, and genetic differences may play a role in the observed race-specific disparities in blastomycosis mortality rates.

A finding of the current study is that even though persons of Asian descent are at lower risk for dying from blastomycosis than whites, those who died from blastomycosis did so at a much younger age (22.6 years younger). This disparity is even greater in the midwestern region, where Asians died at an age 27.2 years younger than did whites.Consistent with the recognized geographic distribution of B. Dermatitidis (,), we found that death related to blastomycosis occurred more often among persons who resided in the midwestern or southern regions than among those in the western and northeastern regions. During the study period, the southern region showed decreases in mortality rates, and the midwestern region, which had the highest mortality rate, showed an increase in rate.The use of population-based data and large numbers can provide insight, though some limitations associated with using MCOD data should be considered.

First, potential underdiagnosis and underreporting of death related to blastomycosis may lead to underestimates of mortality rates and the true public health burden of blastomycosis in the United States. Low physician awareness of blastomycosis may be a contributor. Second, it was not possible to verify accuracy of recorded data or access supplemental data. For example, there may be reporting errors regarding correct race/ethnicity identification on death certificates and in population census reports. Third, we could not adjust for other possible confounders (i.e., smoking, socioeconomic factors, activity, lifestyle, occupation) because these data are not recorded on death certificates. These limitations must be considered along with our findings.This study sheds light on the scope of the incidence of blastomycosis in the United States, though the true incidence may be greater than that reported here.

Dermatitidis infection may be difficult to prevent because of its widespread distribution in areas where blastomycosis is endemic, deaths resulting from blastomycosis can be prevented with early recognition and treatment of patients with symptomatic infection. The continued incidence of blastomycosis in the United States, as indicated by the observed modest decrease in the mortality rates over the 21-year study period, calls for improvement in provider and community awareness, which may lead to including blastomycosis as a diagnostic consideration in patients with pulmonary disease refractory to treatment. Our findings, recent reports of disproportionately high infection rates among Asians , and the lack of decline in the mortality rates in the midwestern region support further investigation.

We also encourage improvements in blastomycosis surveillance that involve examining trends in incident cases, hospitalization (including length of stay), timely diagnosis, and treatment to further elucidate the burden of blastomycosis in the United States.

...'>Blastomycosis In Humans(18.04.2020)Not to be confused with \'South American blastomycosis\'. BlastomycosisOther namesNorth American blastomycosisSkin lesions of blastomycosis.Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by inhaling spores. If it involves only the lungs, it is called pulmonary blastomycosis.

Blastomycosis infections are most common in dogs between 1 and 5. Humans have to contract the fungal disease the same way as dogs:. Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic to areas. A relationship between canine blastomycosis and human disease.

Only about half of people with the disease have symptoms, which can include, weight loss, chest pain,. These symptoms usually develop between three weeks and three months after breathing in the spores.

In those with, the disease can spread to other areas of the body, including the skin and bones.Blastomyces dermatitis is found in the soil and decaying organic matter like wood or leaves. Participating in outdoor activities like hunting or camping in wooded areas increases the risk of developing blastomycosis. There is no vaccine, but the disease can be prevented by not disturbing the soil. Treatment is with for mild or moderate disease and for severe disease. With both, the duration of treatment is 6–12 months. Overall, 4-6% of people who develop blastomycosis die; however, if the central nervous system is involved, this rises to 18%.

People with or on have the highest risk of death at 25-40%.Blastomycosis is to the eastern United States, especially the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, the Great Lakes, and the St. Lawrence River.

It is also endemic to some parts of Canada, including Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba. In these areas, there are about 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 per year.

Blastomycosis was first described by Thomas Casper Gilchrist in 1894; because of this, it is sometimes called \'Gilchrist\'s disease\'. Large, broadly-based budding yeast cells characteristic of Blastomyces dermatitidis in a GMS-stained biopsy section from a human leg.Inhaled conidia of B. Dermatitidis are by neutrophils and macrophages in alveoli. Some of these escape phagocytosis and transform into yeast phase rapidly. Having thick walls, these are resistant to phagocytosis and express glycoprotein, BAD-1, which is a virulence factor as well as an epitope.

In lung tissue, they multiply and may disseminate through blood and to other organs, including the skin, bone, genitourinary tract, and brain. The incubation period is 30 to 100 days, although infection can be asymptomatic. Diagnosis Once suspected, the diagnosis of blastomycosis can usually be confirmed by demonstration of the characteristic broad based budding organisms in sputum or tissues by KOH prep, cytology, or histology.

Tissue biopsy of skin or other organs may be required in order to diagnose extra-pulmonary disease. Blastomycosis is histologically associated with granulomatous nodules. Commercially available urine antigen testing appears to be quite sensitive in suggesting the diagnosis in cases where the organism is not readily detected. While culture of the organism remains the definitive diagnostic standard, its slow growing nature can lead to delays in treatment of up to several weeks. However, sometimes blood and sputum cultures may not detect blastomycosis. Treatment given orally is the treatment of choice for most forms of the disease.

May also be used. Cure rates are high, and the treatment over a period of months is usually well tolerated.

Is considerably more toxic, and is usually reserved for immunocompromised patients who are critically ill and those with central nervous system disease. Patients who cannot tolerate deoxycholate formulation of Amphotericin B can be given lipid formulations. Has excellent CNS penetration and is useful where there is CNS involvement after initial treatment with Amphotericin B.Prognosis Mortality rate in treated cases.

0-2% in treated cases among immunocompetent patients. 29% in immunocompromised patients. 40% in the subgroup of patients with AIDS. 68% in patients presenting as Epidemiology.

Distribution of blastomycosis in North America based on the map given by Kwon-Chung and Bennett, with modifications made according to case reports from a series of additional sources.Incidences in most endemic areas are circa 0.5 per 100,000 population, with occasional local areas attaining as high as 12 per 100,000. Most Canadian data fit this picture. In Ontario, Canada, considering both endemic and non-endemic areas, the overall incidence is around 0.3 cases per 100,000; northern Ontario, mostly endemic, has 2.44 per 100,000. Is calculated at 0.62 cases per 100,000. Remarkably higher incidences were shown for the region: 117 per 100,000 overall, with aboriginal reserve communities experiencing 404.9 per 100,000. In the United States, the incidence of blastomycosis is similarly high in hyperendemic areas.

For example, the city of Eagle River, Vilas County, Wisconsin, which has an incidence rate of 101.3 per 100,000; the county as a whole has been shown in two successive studies to have an incidence of ca. 40 cases per 100,000. An incidence of 277 per 100,000 was roughly calculated based on 9 cases seen in a Wisconsin aboriginal reservation during a time in which extensive excavation was done for new housing construction. The new case rates are greater in northern states such as, where from 1986 to 1995 there were 1.4 cases per 100,000 people.The study of outbreaks as well as trends in individual cases of blastomycosis has clarified a number of important matters.

Some of these relate to the ongoing effort to understand the source of infectious inoculum of this species, while others relate to which groups of people are especially likely to become infected. Human blastomycosis is primarily associated with forested areas and open watersheds; It primarily affects otherwise healthy, vigorous people, mostly middle-aged, who acquire the disease while working or undertaking recreational activities in sites conventionally considered clean, healthy and in many cases beautiful. Repeatedly associated activities include hunting, especially raccoon hunting, where accompanying dogs also tend to be affected, as well as working with wood or plant material in forested or riparian areas, involvement in forestry in highly endemic areas, excavation, fishing and possibly gardening and trapping. Urban infections There is also a developing profile of urban and other domestic blastomycosis cases, beginning with an outbreak tentatively attributed to construction dust in.

The city of, was also documented as a hyperendemic area based on incidence rates as high as 6.67 per 100,000 population for some areas of the city. Though proximity to open watersheds was linked to incidence in some areas, suggesting that outdoor activity within the city may be connected to many cases, there is also an increasing body of evidence that even the interiors of buildings may be risk areas. An early case concerned a prisoner who was confined to prison during the whole of his likely blastomycotic incubation period.

An epidemiological survey found that although many patients who contracted blastomycosis had engaged in fishing, hunting, gardening, outdoor work and excavation, the most strongly linked association in patients was living or visiting near waterways. Based on a similar finding in a Louisiana study, it has been suggested that place of residence might be the most important single factor in blastomycosis epidemiology in north central. Follow-up epidemiological and case studies indicated that clusters of cases were often associated with particular domiciles, often spread out over a period of years, and that there were uncommon but regularly occurring cases in which pets kept mostly or entirely indoors, in particular cats, contracted blastomycosis. The occurrence of blastomycosis, then, is an issue strongly linked to housing and domestic circumstances.Seasonal trends Seasonality and weather also appear to be linked to contraction of blastomycosis. Many studies have suggested an association between blastomycosis contraction and cool to moderately warm, moist periods of the spring and autumn or, in relatively warm winter areas. However, the entire summer or a known summer exposure date is included in the association in some studies. Occasional studies fail to detect a seasonal link.